Despite a tendency to think of personal finance in quantitative terms, helping clients reach their wealth management goals ought to involve more than data-driven models. At Appleton, we believe the best financial planning advice also considers an element of psychology. Recognizing and adapting to unique emotions and behavior patterns can facilitate better long-term outcomes.

Behavioral finance draws upon cognitive psychology to analyze and explain the thought processes that influence financial decisions. This realm of economics challenges what was once a “rational actor” assumption. Improving our understanding of how information is processed, what risk means to each of us, and what prompts individuals to act can help mitigate that which hinders financial planning.

Communication is Essential but Challenging

Recognizing and adapting to distinct communication styles is an overlooked, yet valuable skill. How one person responds to advice is often very different than another. The same substance and style might be well received by one party yet fall woefully short with another. As wealth managers, our attempt to ensure what we say is received in the manner intended requires awareness of and adaptability to the recipient’s communication style. To an analytical, unemotional investor, data may make the case, whereas a less involved investor often makes decisions based primarily on relationship trust. Offering advice in a manner clients can relate to goes a long way towards effective collaboration.

Risk Tolerance: More Complicated Than You May Think

An often-misunderstood reality is that there can be a significant difference between one’s capacity to take on risk and their emotional tolerance for it. The former is means-based, while the latter is a comfort level. While sophisticated models are adept at analyzing risk capacity based on inputs such as wealth, time horizon, and asset/liability modeling, another element lies in risk psychology.

We value objective data such as the consistency of positive equity market performance over long periods, yet also recognize that individual risk/reward frameworks differ. For example, studies have consistently demonstrated that most investors feel the pain of loss much more acutely than the pleasure of gain and may react by “anchoring” to the price paid for investments and resist cutting losses. Understanding a client’s relative comfort level with prospective upside or downside requires understanding how they internalize risk and reward. Absent such insight, susceptibility to behavioral pitfalls such as selling out of markets at the wrong times can increase.

“Experience Is the Teacher of All Things”(1)

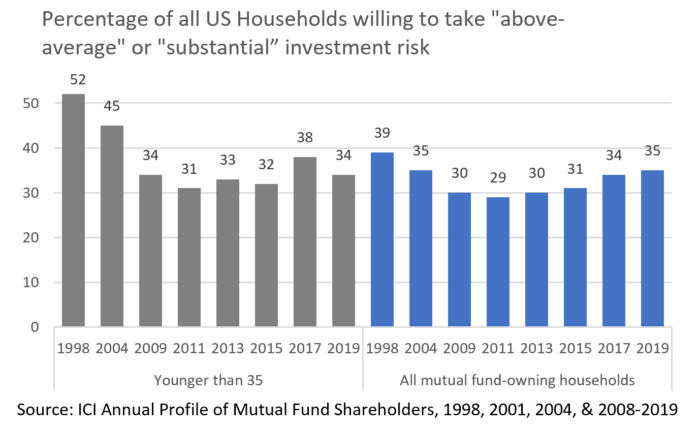

We are all products of our life experiences; the more acute the more likely they are to influence investment behavior. The Great Depression offered an extreme example, as those who lived through that era tended to be highly conservative with their money long afterwards. Recency bias is also a powerful factor. The Investment Company Institute found that willingness to take on risk meaningfully differed depending on the survey year regardless of age cohort. The post-Financial Crisis years of 2009 and 2011 illustrate this point. How a client reacts to an asset allocation plan, and the likelihood they will maintain it long term, may be influenced by the current environment and their past experiences. Although such considerations should not drive a plan’s substance, discussing a client’s emotional ability to adhere to an asset allocation strategy is as much a part of the process as determining their financial means to do so.

“Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow”(2)

Yes, tomorrow will soon be here, so how can advisors address other deep-seated behavioral tendencies that may compromise positive, forward-thinking actions? “Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness”(3) argues that subtle incentives and gentle guidance that preserve individual choice are often more helpful than directives or coercive approaches.

A challenge lies in what is known as status quo bias. Inertia, confusion, or other priorities often inhibit individuals from taking beneficial actions. This is particularly the case when benefits are tangible and immediate (e.g., spending), whereas costs are ambiguous and far removed (e.g., retirement security). The authors make a strong case that mechanisms such as default retirement plan options, negative consent agreements, or eye level shelf space placement are highly effective in inducing advantageous personal decisions without taking away choice. For example, the authors reference a study that revealed how rearranging the placement of school cafeteria items alone changed consumption patterns by more than 25%.

Relative to financial planning, we encourage clients to maximize retirement savings, engage in estate plan review and documentation, and proactively manage taxes. By simplifying decision analysis, offering feedback, and making beneficial options readily understandable, we hope to reduce emotional barriers and “nudge” clients towards constructive actions.

The people side of wealth management may in certain respects be more complicated than its analytical elements, yet both are essential. Personalization extends beyond customizing portfolios; it demands a sense of what makes each client unique and influences their financial decisions. Behavioral finance is an inexact science, yet one that warrants our attention.

(1) Julius Caesar, 52 B.C.

(2) Fleetwood Mac, 1977

(3) Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, 2021

This commentary reflects the opinions of Appleton Partners based on information that we believe to be reliable. It is intended for informational purposes only, and not to suggest any specific performance or results, nor should it be considered investment, financial, tax or other professional advice. It is not an offer or solicitation. Views regarding the economy, securities markets or other specialized areas, like all predictors of future events, cannot be guaranteed to be accurate and may result in economic loss to the investor. While the Adviser believes the outside data sources cited to be credible, it has not independently verified the correctness of any of their inputs or calculations and, therefore, does not warranty the accuracy of any third-party sources or information. Specific securities identified and described may or may not be held in portfolios managed by the Adviser and do not represent all of the securities purchased, sold, or recommended for advisory clients. The reader should not assume that investments in the securities identified and discussed are, were or will be profitable. Any securities identified were selected for illustrative purposes only, as a vehicle for demonstrating investment analysis and decision making. Investment process, strategies, philosophies, allocations, performance composition, target characteristics and other parameters are current as of the date indicated and are subject to change without prior notice. Registration with the SEC should not be construed as an endorsement or an indicator of investment skill acumen or experience. Investments in securities are not insured, protected or guaranteed and may result in loss of income and/or principal.