“Reports that say that something hasn’t happened are always interesting to me, because as we know, there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; . . . we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns — the ones we don’t know we don’t know. . . it is the latter category that tend to be the difficult ones.”

Donald J. Rumsfeld, Former US Secretary of Defense

Some gaffes age unexpectedly well. Donald Rumsfeld’s remarks, widely criticized in 2002 as empty doublespeak, have experienced something of a resurgence. Rumsfeld’s paraphrasing of a NASA framework for thinking about risk has benefited from time and gained wider acceptance. As we close the door on the 2010s and enter the 2020s, thinking about the risks we know, don’t know, and don’t know we don’t know can help frame market expectations.

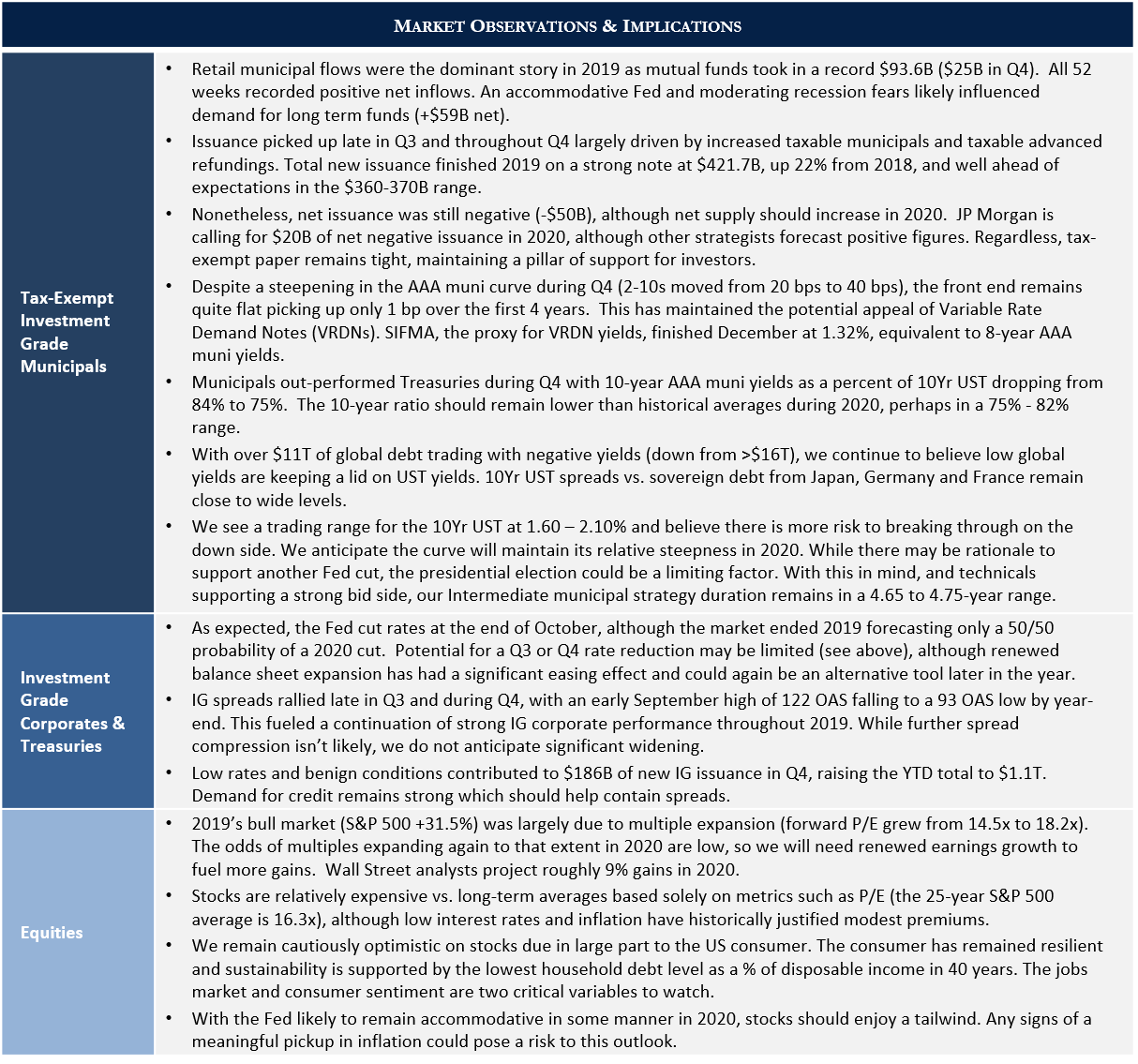

The first step is accounting for “known knowns.” Stock prices are near record highs, and while the S&P’s forward P/E multiple of 18x isn’t excessively stretched, it’s hardly cheap. Likewise, bond yields are low with a year-end 10Yr US Treasury of 1.92% priced much richer than historical averages. Both factors suggest more limited upside for financial assets at the start of 2020 than the beginning of 2010 when the 10Yr UST yielded 3.84% and the S&P’s forward P/E was 14.3x. Coming off a 2019 where pretty much every asset class “worked,” investors ought to expect much more modest 2020 performance.

Any good forecast must also account for factors that could cause results to differ from one’s expectations, and there is no shortage of “known unknowns”. Unemployment is at levels not seen since the 1960s, which has traditionally led to overheating economies marked by wage and inflation increases. However, this hasn’t happened; wage growth is still at levels economists consider sustainable and inflation remains below the Fed’s target. We see room for the economy to expand without prompting upward rate pressure, but also acknowledge the risk that this relationship is merely delayed, not broken.

Meanwhile, the Fed indicates their short-term rate policy is on hold and believes that a hike in 2020 is more likely than a cut. Market participants disagree and have priced in the possibility of a cut before year-end. Recently, disagreement between the Fed and the market has been resolved in the market’s favor. However, the Fed’s willingness to act with a presidential election pending and their political independence already under attack creates the possibility of a policy misstep.

Another unknown is manufacturing, where PMI indices fell into contraction in the second half of the year. Normally this a harbinger of recession, although the American economy has heavily shifted from manufacturing to services over the past few decades. The services economy has remained healthy, a key variable in determining whether growth will continue. Meanwhile, although the US-China trade war has cooled, barriers to trade remain higher than at any other point in post-war history. It’s too early to say how the reversal of the long-term trend towards international cooperation will impact growth.

A third, more positive unknown is the Fed’s quiet resumption of balance sheet expansion in 2019. The impact of prior rounds of QE appear to have contributed to today’s richness in stock and bond valuations. The Fed’s recent injection of liquidity into the capital markets has stabilized the repo markets and supported overall risk appetite. To what extent and for how long this continues is an important unknown.

Last are “unknown unknowns” – factors so far off the radar that they are not understood to be risks at all. These may be unforeseen shocks or the impact of long-term economic transformation. It’s worth considering that while the modern steam engine was developed by 1778, the Industrial Revolution it powered didn’t begin until 1850, or that the electric motor was invented in 1821 yet it would take nearly 75 years to drive the Second Industrial Revolution. Seemingly mature technologies like the computer or the internet have long permeated our economy, yet history suggests the greatest impact may still be to come. Newer technologies like blockchain and artificial intelligence may have revolutionary impacts in ways that today are difficult to imagine let alone forecast.

Putting it all together, a reasonable “base case” for the coming years would be positive but more muted stock and bond returns, with GDP growth slowing but not stalling. This is a sensible point to start an investment plan. However, there are no shortage of “known unknowns”, as well as “unknown unknowns” capable of fundamentally altering the status quo. Acknowledging the risk of deviation from a forecast is another way of saying that portfolio diversification is critical, and that an investment plan should account for not just what you know, but also what you don’t. “Sticking to your knitting” while carefully monitoring changing market conditions helps lessen the risk of portfolio shocks, foreseeable or otherwise, in the hope that with time your portfolio will age as gracefully as the cryptic remarks that open this letter.

Tariffs also tend to boost inflation. This is primarily driven by how sensitive consumer demand is to changes in price; the less sensitive, the more of the tariff will be passed on to domestic consumers. Yet surprisingly, inflation has remained muted. This appears to be due to both participants’ negotiating strategies; the Trump Administration made a conscious effort to minimize consumer impact over the first few rounds of Chinese tariffs, while the Chinese have focused their retaliation on goods and sectors to maximize immediate US economic effect. For US consumers, if the deflationary effect of lower Chinese demand for US goods is bigger than the inflationary effect of tariffs being passed along on Chinese imports, then the total impact would indeed be muted inflation. We argue this has been the case – so far. However, the initial round of tariffs that are likely to introduce greater acute consumer impact are just now coming into effect.

Economic forces will only partially influence how the trade war evolves and markets ultimately react. What economic theory tells us, however, is that tariffs alone won’t solve this trade war. They will likely have greater impact on economic growth than trade deficits. The US and China have weathered the slowdown reasonably well to date, and we’ve been pleasantly surprised by the resilience of US consumer spending. Nonetheless, as investors, we’d like to see healthier growth with fewer economic and market headwinds. This would likely contribute to a modest but productive steepening of the yield curve, while bolstering consumer and business confidence. As US and Chinese representatives prepare to once again meet, we are hoping for greater stability in the form of a trade truce whereby both sides refrain from additional tariffs.

Arguably, though, the root of the issue here is how accustomed we’ve grown to discussing trade in military terms. Thinking about it in this way encourages thinking of trade as an adversarial process where every winner requires a loser. This framing doesn’t really work; however convenient the metaphor, tariffs are not torpedoes that can be aimed at one participant while sparing all others. If imposing trade barriers causes mutual harm, reducing them should provide mutual benefit, both to consumers and investors. These benefits are something we’ve perhaps come to take for granted. Trade barriers have progressively fallen since the Second World War, as the global economy has become increasingly interconnected. While there are still trade abuses, we feel needlessly reversing this trend will be harmful for the global economy and markets. And in the meantime, maybe it’s time we drop the trade war metaphor in favor of something a little more cooperative.